To view this content, you must be a member of Mathew’s Patreon at $1 or more

Already a qualifying Patreon member? Refresh to access this content.

I actually think this might be the worst one of these?

I say this as someone who has sat through Eternals, to which this movie, bafflingly, decides to be a direct sequel. If the MCU is going to start binning off things like Kang, they’ve really got to suck it up and start retconning entire movies and TV shows that haven’t worked out. They happened in a different universe or whatever. It’s unfair to force me to remember things that suck.

I suppose the joke is on me though because I still watched this. It feels like the kind of granularity required here is unnecessary, but watching this you understand there’s a difference between “soulless content” where people might have had “ideas”, “concepts”, perhaps even a “mindset” and “goals”–in films as bad as the aforementioned Eternals, or The Marvels–and something that seems to have been cobbled together for no other reason than to exist.

It’s entirely possible this was intended to continue the kind of “vaguely spy thriller” feel of the earlier Captain America movies, which was pounded into mush by five different writers, countless more rewrites and reshoots, ending with what’s barely a conspiracy with a shifting reason from a hidden mastermind whose reveal leads to the kind of reaction the word “nonplussed” was invented for (unless you just laugh at how stupid he looks. How can you treat Tim Blake Nelson like this?)

Like: this is a movie where a bunch of characters get Manchurian candidated, attacking when they hear a particular song, and no one says “did no one notice that song playing suddenly before all hell broke loose” in any of the sequences where they’re trying to defend the people who went loco.

But I’m getting hung up on details in a movie that even visually has no connection to reality. It’s insane a movie looks this bad. The first fight scene doesn’t have the impact a regional filmmaker working in his own backyard could manage, and every dialogue sequence makes it look like they didn’t get access to the Volume so they asked Neil Breen if they could use his setup. They compensate by making the lighting so flat and bright that for all I fucking know they might actually have been some of those places.

Ah man. I can’t resist pointing out that the climax of the opening scene is that Sam has to fight… a large man. Like just a big guy. I guess he has a beard? It’s so hilariously underwhelming. Later action sequences are no better, completely weightless and because of the complete failure of narrative, absolutely stakes free. Like… we all know you can’t beat up a hulk, so why are we watching a character attempt it for about twenty minutes?

I suppose the main thing that’s interesting about this film is its politics, which manage to split the difference between “milquetoast” and “completely toxic” somehow. I’d be very interested to know how everything here got shaped into a movie where the first Black Captain America says things like “sure he threw me in prison and let you be experimented on for 30 years against your will, but he’s the president and we should trust him now!” which manages to make Falcon And Winter Soldier (which really copped out by the end) almost look revolutionary.

It doesn’t help that one of the major character here is based on an explicity Israeli nationalist superhero, played by what appears to be an Israeli child with progeria whose make-a-wish was to be in a Marvel movie (I assume after having their top choices, “I’d like to blow up a hospital full of children sicker than me” and “make the IDM mixes I post online popular” turned down.) I like the way they pointedly say “none of us have to be defined by our past” without saying anything like “it’s doing the right thing now that matters” because, well…

Really the moment of this movie that stands out the most to me, though, is when Sam stands meekly by while an old black man is roughly thrown to the ground by cops, mustering up the strength to shout something like “wow, be gentle!” which the cops completely ignore. I’m not sure a Marvel hero has ever seemed more pathetic. You feel a deep sense of embarrassment watching it, and, to be honest, throughout the film. You ask yourself, what were these people thinking? And you realise: nothing. these people were thinking… nothing.

Follow Mathew on Letterboxd.

Developed/Published by: Infocom

Released: 22/08/1986

Completed: 18/04/2025

Completion: Completed it. 304/304 points (though points are random and I believe you get them all just in the process of beating the game.)

Phworr, eh lads? Etc.

Right, that’s me got all the 90’s video game magazine parlance out of the way [“you forgot ‘or something’ and to do a made-up Ed’s note”–made-up Ed.] so I can put my “pretending to be a serious games historian” hat on for the first Infocom game I’ve played since Trinity–surprisingly, all the way back in 2023. If you’ve been following along, you’ll be aware I’ve been picking and choosing Infocom games to play through, leaning towards the work of Steven Meretzky, and I’ve been looking forward to playing this for a while, his “return” to a more normal sort of adventure game after the big swing (and commercial miss) of A Mind Forever Voyaging.

Based on a joke title Meretzky posted on a whiteboard featuring upcoming releases for Infocom, Leather Goddesses of Phobos is a strange release, I think. Infocom had always made games for adults, but never “adult” games, and there hadn’t really been any commercial “adult” games for years at this point. Softporn Adventure came out in 1981, and unless you’re Portuguese and have fond memories of Paradise Cafe for ZX Spectrum that was about your lot. So it seems like quite a gamble for Infocom to release something that appears so risque–but then Leather Goddesses of Phobos isn’t really an adult game at all. In fact, it’s barely smutty at its most extreme, and Meretzky, wanting to drum up a bit of controversy after the failure of an anti-Reaganite art game, decided “sex sells” and Infocom as a group went for it: digging through Meretzky’s papers, he sent a sheet of possible game ideas to the other imps (this may have been the standard procedure at Infocom?) for his next game, and Leather Goddesses of Phobos won out, where its sexual content was expressed as “very soft-core; see Barbarella as an example.” (it doesn’t even go that far, to my eyes.)

(The sheet is quite illuminating in general, a kind of ideation that I recognise as a game developer. We have another attempt, I think, to court a bit of controversy with “The Interactive Bible”, an interesting if not-yet-fully-baked design idea “Blazing Parsers” and then something that’s optimistically trying to make making a game quicker, “The Viable Idea.” Personally, I’m sad we never saw an Infocom spaghetti western.)

Unlike some other Infocom releases, I don’t really have any personal history with Leather Goddesses of Phobos outside of memories of the (very) mildly titillating screenshots of its sequel, Gas Pump Girls Meet the Pulsating Inconvenience from Planet X! In fact, the main thing I have to say is that I only realised this wasn’t called “Leather Goddess of Phobos” after playing it for a bit, which won’t make me cry “Mandela Effect” as much as “Goddesses is such an inelegant word, it’s bizarre it isn’t just Leather Goddess. My brain was correct, reality wasn’t.”

But anyway, what is it actually like to play Leather Goddess(es) of Phobos?

I’ve been a bit up and down on the Infocom games I’ve played–some might say unnecessarily hard on them, judging them by the coddled standards of 2025. But Leather Goddesses of Phobos gets off to a good start. Unlike Trinity, where you essentially never know what you’re actually trying to do overall, Leather Goddesses of Phobos more or less immediately has a character hand you a laundry list of items to collect, and then you go “oh, I guess I just have to collect these, then.”

As good as that is, it’s also a little… underwhelming. Having picked and chosen, I’m aware that I’ve not seen everything that Infocom has to offer, but I’m still surprised that I haven’t played an Infocom game since Deadline (their third game) that gave me any sense of anything except a static world. Leather Goddesses of Phobos gives you a Floyd-like companion (Trent, or Tiffany) but they barely seem to exist, and even when you meet characters in the world they feel so… un-interactive. Maybe, at best, they take part in a little vignette.

I suppose with Leather Goddesses of Phobos I’m really realising–and perhaps chafing against–the limitations of the text adventure at least in the mid-1980s. In some respects, you want a text adventure to have the feeling of a book; limitless, enveloping imagination. But in other respects, you want to play it like a game. You want to be reacted to. It’s probably, why, to be honest, characters have been so sparse in these games–because when you try and interact with a character, and they don’t do anything, or it feels wrong, the illusion of being on an adventure is broken. You’re not reading a book, you’re on a dark ride and suddenly the lights slam on and you’re aware you’re looking at a mannequin, not the king of Mars.

Somehow, the fact that characters in Deadline might like… walk into another room just abated that, and I’m not asking for characters to roam across the planet here, but maybe if they piped up a bit more. Felt a bit more worth talking to. The issue with making a “funny” game is that so much of comedy is character work, and here, really, the only character is the parser.

But I’m being a bit harsh, because Leather Goddesses of Phobos is otherwise an extremely solid classic rooms and items, bread and butter text adventure. The best I’ve played since Meretsky’s own Planetfall, and arguably the best I’ve played full stop. It’s understandable, accessible, and I never had to use an Invisiclue to the point where it just told me what to do–well, except in one particular case.

That one I’m just going to spoil, actually. One of the things that makes Leather Goddesses of Phobos work so well is how well integrated the feelies are. Sure, I don’t have the box to hand, but there’s a comic which includes a couple of direct hints for some puzzles, a map which is unbelievably necessary and helpful, and a scratch and sniff card, which I’m sure nearly 40 years later is completely useless even if you opened a brand new box, but which is a really cute and silly B movie-adjacent idea that’s perfectly fitting. One of the things it does is prompt you to “smell” things in the game to work out what they are (which it thankfully tells you in text–scratch and sniff cards have always barely worked). Early in the game (for me–the game is fairly open ended) you sniff and discover some chocolate, which, of course, you’ll hang on to. Later, for reasons, your mind will be transferred into a gorilla. But you’re not strong enough to break out of the cage. I assume you can see where this is going: you need to eat the chocolate to get strong enough to break out of the cage.

You know, that famous thing about gorillas. That chocolate makes them strong.

This is, obviously, nonsense. The only animal-related fact I know about chocolate is that it kills dogs and I certainly wasn’t hanging onto it in the game expecting I’d use it to kill a poodle or something [“you said ‘or something’ after all”–90s Ed.] Considering that banana is one of the most recognisable smells you could possibly use on a scratch-and-sniff card, I had to assume that Meretsky simply thought that giving you a banana would be too obvious a solution so went with the impossible to work out chocolate, but I couldn’t find anything in his notes to reflect that. According to the ever reliable Digital Antiquarian, Meretsky tested the scratch and sniff scents on the other imps to select the most recognisable scents to then use in the game, and I do think it adds insult to injury that one of those chosen scents actually *was* banana! But it’s used elsewhere!!!

I even found a playtester who complained about this exact puzzle:

“It is reasonable to not eat the chocolate and even suspect the sugar rush, but why oh why would you put the chocolate in the cage?”

I suppose he’s more complaining that this game features more than one puzzle which requires hindsight, and to be honest, they should have fixed those too. But in general, Leather Goddess of Phobos is logical and fair, while still managing to make puzzles funny and clever–the best of The Hitchiker’s Guide To The Galaxy without the worst of it. There’s a puzzle about kissing a frog that will immediately put you in mind of the famous babel fish (and which made me laugh out loud) and a puzzle involving a mysterious machine and wordplay that is so perfect and silly that it’s maybe one of my favourite things in an adventure game ever–possibly worth the price of admission alone.

The game does still undercut itself though–for seemingly no reason. There are definitely ways to manufacture yourself a no-win, dead man-walking situation, for example, all of which I miraculously managed to dodge due to the order I did things in, and I definitely had a few puzzles where by all rights I was just lucky to not have to resort to clues. One object on your list you need to specifically look somewhere you might not look to find, and then you need to be really specific with the parser to do what you need to do to get it. Another requires a vignette that you need to be in time for (though that one I immediately sussed what was up–the “dead end” was just so suspicious to me. But I reached it almost at the end of the game–if I’d got there early, I could have had to replay nearly the entire game.)

The game’s maze–which people find famously annoying–is a perfect example of how the game undercuts itself. You have the map in hand. You have the required clue. If you’re patient, it’s actually really satisfying to navigate it, and I did so… and then the torch I was using burned out, and I had to do the whole thing again much more efficiently. Close to hundreds of turns. It was so unnecessary! I was having fun!!! Why punish me for not being perfect!!!

These moments, however, are far rarer than you’d expect. I noted above that the game is fairly open ended, and I’m not sure if there’s a “preferred” way to work through the game, but as I said above in my playthrough I never entered a vignette where I didn’t have something to hand I needed (though it’s possible, I’m sure) and if I got stuck somewhere there was always somewhere else to go for me to solve something else. I never put this down annoyed–well, apart from the fucking maze. Well, not the fucking maze–the fucking torch (I honestly did think the maze was clever.)

I think the thing about Leather Goddesses of Phobos is… it’s probably as good as one of these things is going to get without a much more modern design philosophy. You know what you need to do and every time you sit down and play it you get a little closer to doing it–and it’s charming while you do it. But it’s never sexy. I did play it on the “LEWD” setting and took every opportunity for a bonk, because I’m still thirteen at heart, but my dander remained unfrothed; it doesn’t even reach the heights of Alter Ego! I guess I’ll see how I get on with [checks to-play list] Leisure Suit Larry??? Eugh!

Will I ever play it again? You know, it’s possible. It’s not likely, but it’s possible. And I will play Gas Pump Girls Meet the Pulsating Inconvenience from Planet X!, which I don’t believe anyone likes. Because why not.

Final Thought: In some respects, Leather Goddesses of Phobos suffers for not being something special like A Mind Forever Voyaging, but it also sort of is, as the last true success Infocom would release before the company began an unstoppable slide into oblivion, and for that alone it should be celebrated. At the very least, if you like text adventures, though, you know how to play them, and you can live with the idea you might have to reload a save on occasion, this is a solid couple of tevenings. Oh sorry, I mistyped… tevenings. There must be a mysterious machine around here somewhere for that…

The Internet is dead.

This is not a eulogy, but an acknowledgement. An acknowledgement that what I’ve come to accept the internet to be is dead. An acceptance that in the name of ease, I’ve absorbed myself into a corporatised space that is at this point not simply eating itself but eating me, us and everything that we create.

And I think: fuck it.

In 2023, when I started publishing exp. again in print, I was, I think, trying to close my eyes to it. I liked–and I still like, I love–the purity of print, the focus. I still want to make things and put them into the world. But I also just love writing, and sharing it. For a long time, I’ve relied on existing sites for my work–be that big platforms or outlets, but of course what happens is they pivot, they get sold, they get erased. And it can feel like we’re always searching for a settled high ground–Bluesky feels great now, but is it just a little rocky outcroppings in poisoned sea, bound to erode or be subsumed?

At the end of 2024 I published Every Game I’ve Finished 14>24, which I think works as a nice culmination of my last decade of writing. But as I’m not going to stop, it seems necessary in our new dead internet to do something that I’ve been meaning to do for ages, which is plant and cultivate my own space properly and invite you to visit it. Not just hope that you’ll see something I’ve posted as you scroll, but offer something that you can actually choose to engage with. Where my writing finally stays, where you can properly search and explore it, where I can expand beyond what I’ve been doing if I like.

I think there’s a danger of nostalgia here, some sort of limiting call back to the idea that you’d, like, log on the internet and type “https://www.expzine.com” in every morning after you’ve read the three or four webcomics you keep up on (wow, Superosity is still going!) but I think that’s why I’ve become enamoured with the mindset of POSSE–Publish On (your) Site, Share Everywhere–and using it to its fullest. So I’m going to be posting here, then spreading this to every part of the stupid corporatised internet I can be fucking bothered with. Let decay feed growth.

To support that, I have (sorry) started a new Patreon with refreshed tiers to accompany my currently existing Ko-fi that has been supporting the continuation of my writing and publication of my zines and books. Unfortunately, Ko-fi’s tools aren’t robust enough, so this seems to be the simplest way to offer new articles to supporters on this site first, so if you aren’t already a supporter, please check it out.

(Something worth emphasising I’ve continued to set the lowest tier at just $1 a month–so it’s as little as $12 to support the only* video game criticism website on the internet)

*as far as I’m concerned.

If you are already a Ko-fi supporter: you don’t have to do anything. You can continue to support me on Ko-fi and I’ll be sharing articles–in full–over there a week early as usual. But if you’d like to move over to Patreon, I’ll be sending you a free month of the tier your current donation is equivalent to, so you don’t feel like if you want to switch over you’re being double charged or anything.

If you don’t want to support, that’s fine! You could just sign up for the newsletter, which is going to remain free and collate the posts of the week plus some extra waffle. Probably, I haven’t really planned them yet.

And if you don’t want to do any of that, I’m not entirely sure why you’ve read this far. But the point stands: if you don’t like our dead internet, grow your own.

Developed/Published by: Supergiant Games

Released: 20/05/2014

Completed: 10/04/2025

Completion: Finished it.

It’s been a couple of years since I went through Bastion(!) so I thought I’d boot up another Supergiant game, and decided to just move forward chronologically when I checked and saw Transistor was pretty short–I just keep putting off anything that seems like it’s going to take ages to complete these days. Plus it’s always nice to see how a studio evolves.

Not knowing anything about it, I assumed–what with the isometric graphics, and the lady with the big sword–that Transistor was “more Bastion” in terms of being an action title with light RPG elements, but it’s actually something much weirder–an awkward meld between Bastion-style real-time mechanics with a turn-based battle system that’s similar to something X-COM, or more specifically like Valkyria Chronicles, with free movement and action-point system.

I’m so sincerely not a fan when promo screenshots hide all the UI–in Transistor’s case, they go as far as completely hiding the entire battle system (which looks like this.)

There’s also a bit of the deckbuilder to it. While the game doesn’t have a huge or ever-changing range of abilities, each time you level up you select new abilities and each is able to work as an action on its own, an upgrade to another action, or a passive ability, leading to a pretty wild amount of combinations which are meant to emphasise your chosen playstyle. So you can double and triple down on your favourite ability by adding upgrades and passives that support it, or you can try and make a “hand” of abilities that work in conjunction–maybe you want to tank damage; maybe you want to be a glass cannon, maybe you want to spawn helpers or play stealth. It’s all some amount of possible.

It sounds really good, and interesting, but I’m sad to say it doesn’t work, because the combination of real-time and turn-based combat is never comfortable. It’s not so much like eating a chocolate and peanut butter cup as trying to eat spoonfuls of peanut butter while chocolate pours from a faucet that you can’t turn off. The game seems to be balanced around using your turns in a tactical manner, but you have to wait for your action points to regenerate in real time. You are defenceless during that period (unless you upgrade one of your abilities to be used during recovery) so you’re stuck running around being attacked until you can get back into a turn.

This isn’t fun at all! The enemies are fast and the action frantic, so any time you’re not in a turn you feel like you’re barely keeping your head above water, soaking up damage. I’m sure there are mitigations, and it’s entirely possible if you’ve played this you created a hand of abilities that made the experience smooth, but Transistor really fails at explaining anything about how to play it.

It’s probably part of the game’s storytelling–it starts in media res and slowly reveals what’s going on–but it feels like there’s no help in getting comfortable with the mechanics. There’s a “backdoor” area that appears periodically where you can take part in “tests” that throw you in at the deep end so you can learn by trial and error what different abilities do and how to combine them, but I’ve finished this and I’ll say that I’m actively unsure if I ever played this game correctly. I ended with a build focused on long turns to allow me to debuff and do massive melee damage, which sounds really rewarding, but I still spent most of the time taking damage and running away, even with one attack set for use during recovery. If that’s intentional, I just don’t get it.

The upgrade system really probably does have too many options and is fussy to interact with.

It really feels like one of those designs that someone came up with because it sounded good, and then you get to this point in development where you have it all built but you can’t find a solution to a problem like “what do people actually do while waiting for turns to recover” because the core of the design, ultimately, just doesn’t meld. It seems likely they found people being able to use all their abilities in recovery (for example) made the turns either unimportant or overpowered and then couldn’t solve it so just powered ahead because it roughly works. I’ve watched a few playthroughs of Transistor and everyone else seems to have played it similarly to me–different abilities, but same tactics. It doesn’t really look any more satisfying a play experience than the one I had, which is a bit of a shame for a game that puts such effort into having an insanely modifiable range of abilities. You just never feel like you’re excelling, just surviving.

To speak positively, Transistor’s arms-length narrative did grow on me. I think largely down to the performance of Logan Cunningham as The Transistor; he sells the game’s noir-like setting while expressing deep pathos; he’s talking to someone he loves, and you can always hear it in his voice. You could argue it overpowers everything else in the game; the enemies have no character and the main antagonists are barely there. The central characters are the only ones you’ll care about–thankfully, they’re sensitive to that, and when the game ends, at least that feels satisfying.

Transistor really isn’t a game I could recommend, though, even as short as it is. It just doesn’t come together.

Will I ever play it again? I’m generally glad when a game includes a new game plus, and while I could unlock more abilities and so on, this is one of those stories that feels like such a nice closed loop, why ruin it by playing it again? Never mind that I didn’t actually really like how it played that much…

Final Thought: A thought you might have about Transistor is “why isn’t it just totally turn-based?” but it’s obvious once you’ve played it for a while that the overhaul required to make enemies work and balance it would be almost an entirely new game. Sometimes you just go down a path and there’s no going back.

Developed/Published by: Jon Ritman, Bernie Drummond / Ocean Software

Released: 05/1986

Completed: 01/04/2025

Completion: Finished it. God help me I finished it.

It all seemed so simple.

Jon Ritman and Bernie Drummond’s “Head Over Heels” is a big video game (or should I say, computer game) in the personal history of Mathew; bought because it was so lauded in the likes of Amstrad Action, it really did blow me away once I played it: a true adventure featuring two protagonists with different abilities that you have to use together. It seemed like a work of genius to me.

So when I was looking over 1986’s releases, I noticed the pair’s previous isometric action adventure, Batman, and thought it might make sense to play. See if the magic of Head Over Heels was there from the beginning, and set the table for a replay of Head Over Heels at some point in the future.

I’d consider Batman a bit of a joke in the non-UK gaming community, probably because anyone who is looking up Batman video games is going to discover that the first Batman game is a ZX Spectrum release that features Batman wandering around an isometric, bizarrely decorated Batcave looking for parts of the “Batcraft” where the enemies look like melted dogs and basically touching anything kills you. It’s just so weird, lol!!!

What’s generally forgotten in the discussion is that in the mid-1980s, no one gave a fuck about Batman. It had been nearly twenty years since the TV show and Wikipedia notes that even Batman comics circulation had reached an “all time low” by 1985. His fortunes would turn around rapidly–The Dark Knight Returns would actually start being published before Ritman and Drummond’s Batman would come out–but considering the era, from Ocean’s perspective it will have been an opportunistic gamble: grab a cheap license on death’s door and try and squeeze some more juice out of it. And they did give it to one of their best developers, who’d already given them a lot of success with the Match Day franchise. Clearly it wouldn’t matter too much that he could barely remember who Batman was…

Anyway–I’m just going to cut to the chase here and say that this took me about six months to finish, and as a result I’ve lost most of the specific game history I’d dug up about it and all that remains is a lot of vague “I read somewhere that Ritman said…”. So don’t quote me on anything but my memory is that Ritman has been quoted as saying that he wanted to best Knight Lore, and then Drummond came in and started drawing like a cyclops head with flippers and he was like “alright!”

Knowing this, I should probably have played Knight Lore first, but getting into Rare’s entire back catalogue would be a whole other thing, so I can just say that even with a prior understanding of the isometric action adventure, Batman is a brutal experience.

First things first: it’s really hard to parse visually on the original ZX Spectrum. The environments are surprisingly detailed, but because it’s all in monochrome, it’s really quite hard to discern what everything is, and no way to tell what’s going to kill you when you touch it. I had hopes that the Amstrad CPC version with its wider range of colours might fix that, but there’s no consistency from room to room so it sort of just looks insane.

If you want to play this in 2025 with normal human eyes, there’s a fantastic remake by Retrospec (that’s, er, fifteen years old itself), or you can go back and play “Watman” a DOS remake from 2000 (so closer to the release of the original than now.) However if you’re really determined to play this (which I don’t recommend) what I recommend is to play the MSX2 remake. It’s pretty much what you’d imagine the ZX Spectrum original to be if it had full color–right down to the performance.

And, of course, then you get the ability to quicksave and load, because without that I’d have never been able to finish this in a million years.

The version I played looked like this. Significantly easier to parse.

It’s not simply that Batman is full of things that kill you. It’s that the game is designed to force you to play perfectly from the first screen. Enemies seem to have a truly random movement routine (hope you love shuffling around waiting for them to select a direction away from you) but that’s not an issue as much as that there’s no leeway in the collision detection, and in fact the game is designed around that, generally requiring that if you want to make a jump you actually have to position Batman so he’s got about one pixel left on the platform he’s “standing on” so you can reach the next. Hilariously, the manual makes excuses for this:

“To make certain jumps it is necessary to hang by the ‘merest thread’ on the edge of the Carbon Re-inforced Batcloak – you may need practice to perfect this feature!”

(This isn’t even the funniest excuse in the manual, which also notes “The Joker and the Riddler do not appear ‘in person’ in the game, as Batman is all too familiar with their image. The henchmen they have selected are unfamiliar to Batman and this further complicates his task.”)

So yes, the game is exacting. And with 150 rooms to explore, it’s also bloody confusing. It’s actually not as non-linear as you might think–a lot of directions you go don’t really head anywhere–but once you get deeper into the game your head will spin, and every game over feels like being kicked full in the groin when you realise how difficult it’s going to be to get back to where you were (although the game features a save system of sorts based on when you pick up particular collectibles, it’s unforgiving at best.)

And on top of all that, the puzzles are intense. I will have to go back to Knight Lore to see just how complicated things are there, but it’s a bit like when you go back and look at things like Wizardry or The Bard’s Tale. You’d expect that these genre originators would be simple, but somehow they’re significantly more complicated and off-putting.

Here, you can sense Ritman almost understanding how to provide an on-ramp for players as the game is designed that you first collect Batman’s gear, slowly growing his abilities as you go (you can’t even jump at first) in a smaller section of the map that’s particularly linear. But one of the very first puzzles will kill you multiple times because it requires that you walk the wrong way on an invisible conveyor belt and then do a pixel perfect jump????

It soon gets absolutely absurd. I’m not going to lie. After beating my head against this game for months off and on–struggling to understand the maps I was able to find (isometric maps on paper are confusing!)–I eventually just started watching and carefully following someone’s playthrough on YouTube (a playthrough that, notably, they die a bunch of times on.)

I usually love using contemporary maps and walkthroughs. But you try and work this from Amstrad Action Issue 9 out (it spreads over two more pages!)

This revealed to me that certain screens had insanely unintuitive solutions that I just don’t think I’d ever have worked out. The screen where you have to catch a wizard’s hat and then catch an enemy on top of said hat otherwise they’ll block your path. The screen where you have to manipulate several teapots to reveal a completely hidden piece of the batcraft. Or my favouite, the screen where you have to time dropping a spring on the top of an enemy’s head so you can ride them and jump off at the right time to get to the exit???

I have no idea how anyone did any of this in the first place. Playing Batman has to be ones of the most demoralising gaming experience I’ve ever had, genuinely feeling like being trapped in a carnival funhouse until I can solve a rubik’s cube while a car alarm goes off (don’t play this without making Batman’s footsteps silent…)

I’m aware, though, that a lot of people don’t feel this way, considering it’s been remade so many times! Which actually makes me extremely worried that Head Over Heels isn’t the masterpiece that I remember it being.

Well, guess I’ll find out soon enough!

Will I ever play it again? I played it more than anyone ever should.

Final Thought: Certain things just aren’t worth beating, and I’ve definitely given up on things before, but my fealty to my memory of Head Over Heels really was overpowering to the point where I thought I had to, that I would simply find something here. And to be fair, by the end of my playthrough, I was dying far less, and I could probably get through a significant chunk of the game now legitimately if I really wanted to.

I really, really don’t want to.

Please don’t make me.

Developed/Published by: Nintendo

Released: 01/05/1984

Completed: 30/03/2025

Completion: Finished 10 courses–there’s no ending.

Another early NES title that seems to go largely unremarked and unremembered, Mach Rider surprises me because since I began working through all the games I own/have access to in (vague) chronological order, this this is actually the earliest raster-scrolling racer I’ve played. I mean, of course in my history I’ve played Pole Position and the like, but I guess I just assumed I’d have had easy access to something more iconic in the genre before this. You can argue that Super Hang-On counts, because the original version of Hang-On was out before this, but it feels like a bit of a cheat. And indeed, I’m now quite baffled that Pole Position wasn’t included in Namco Museum for Switch.

And now I’m remembering the Pole Position TV show and its banging theme song. Can you believe that it only ran for 13 episodes and it’s completely seared into my mind? I really wished they’d make toys of the cars when I was a wean. Ah well.

(You’re here for these digressions, right?)

To get on topic, Mach Rider is a strange one because Nintendo passed up releasing F1 Race, a much straighter racing game, in the West, and released this as the first racer on the system. But it’s not, exactly, a racing game. In Mach Rider, you play the titular hero in the year 2112 [“Rush Klaxon!”–Canadiana Ed.] who is racing across a devastated future landscape looking for survivors. Your superbike is equipped with four gears and forward guns, and as you race you have to avoid, shoot or bump off course enemy “quadrunners” while also avoiding ice, oil slicks and other debris in the road.

Most unusually, the game has a strangely split design in its story mode (“Fighting Course”) where for some reason on the first level you are racing with energy counting down, and you can’t game over (unless the energy runs out) but the quicker you can finish the level the more lives you earn for the rest of the game, where you can game over. I’m not entirely sure why this is, but it might have something to do with the major secret of Mach Rider.

You see, the first time you play Mach Rider–and probably for a bunch more goes, maybe all the goes you ever have of Mach Rider–you’ll notice something. It’s hard as balls. Actually–it’s unfair as… is there a kind of ball that’s unfair? Lottery balls? It’s as unfair as lottery balls (you can use that one if you like.)

I love a rear-view mirror in a video game (who doesn’t remember the one in Rad Mobile, with the Sonic toy dangling away from it) but here you have to really pay attention as you immediately die if you collide with anything that you aren’t at least matching speed with. What this means is that you really need to be taking the courses at full speed because otherwise cars just shoot up behind you and crash into before you can do anything. But if you are going at full speed, when you go around corners you can’t see and react to, say, rocks or barrels in your way, so you just crash into those before you can do anything. It could be said you’re in between a rock and a hard… car.

This feels… rubbish. You can get into a groove of, say, racing along in third gear, going up to four when someone is on your tail, and then slower on corners, but it can’t protect you from completely unseen hazards particularly well, and you will, probably, put the game down in frustration. Because it’s just sort of annoying.

But I mentioned Mach Rider has a secret: a power-up system that I doubt many know about because it features such a (sigh) Tower of Druaga-esque series of requirements:

Now, I honestly thought this might be made up because the requirements seemed so stupidly hard. But on the first level, you have the ability to practice without fear of game over, so if you just start by slowly shooting three drums and then practice on the course you can eventually unlock the invincibility and then… Mach Rider becomes quite playable!

Now, you do lose these power ups if you die–but you might not have that many lives to begin with, and the invincibility makes the game close to trivial as you can blast through all the levels in fourth gear, only really having to worry about bomber balls, which can still kill you out of nowhere (the main reason you probably want to go out of your way to get autofire–but it’s much harder to get that consistently or consistently early.)

It’s like the team at Nintendo–or rather HAL, who put this together–couldn’t really work out a way to make the game not frustrating without making it too easy, so they bodged in a system where the pro-strat for Mach Rider is to get really good at unlocking the first power-up on the forgiving first level and then hang onto it for dear life.

I suppose it doesn’t really matter–the game doesn’t have an ending (you do ten levels, then there are ten more, then it just loops) so the game is ultimately only a score attack. But I don’t know if I’ve ever played a game like this before–one where it’s passable if you know one weird trick and absolutely rubbish if you don’t!

Will I ever play it again? I gave myself a cheeky save state after the first ten levels but I don’t see much reason to go back.

Final Thought: Mach Rider is ostensibly named after a toy Nintendo put out in 1972–a hot rod racing toy that they licensed from Hasbro–but I don’t see any meaningful connection between them. It’s possible Nintendo used the name simply because they had the trademark?

More likely though I think they used it because the game feels so inspired by the always popular Kamen Rider–the Mach Rider even sort of looks like a Kamen Rider, and included a setting inspired by Mad Max (which also featured biker gangs.) One could even posit that “Mach” and “Max” sound a bit alike.

(But that last one doesn’t really work because Mach Rider is transliterated as “Maha Rider” in Japanese.)

Developed/Published by: Dogubomb / Raw Fury

Released: 10/04/2025

Completed: 22/04/2025

Completion: Entered room 46.

I have great respect for the craft and effort put into Blue Prince.

But I don’t think Blue Prince respects me.

…

Before I dig into that, let’s actually explain what Blue Prince is. At a high level, it’s a puzzle adventure deck-building rogue-like-like (phew) in that it takes design cues from things like Myst or the 7th Guest. So you wander a mysterious location–in this case, a stately home–solving logic puzzles and pulling levers in the hope they do something you can at least vaguely understand, all in an attempt to get to the “antechamber” room you can see at the other end of the map.

However, in this mysterious location, every time you enter a new room, you place that room on the map from a “hand” of locations drawn from an (unseen, but slightly manipulatable) deck. Rooms feature up to four exits (though may be dead ends) and can contain puzzles, objects or actively negative effects, and can influence other rooms. So, for example, you can draft a utility closet and turn on the power for the garage, whether or not you’ve drafted it already–so you might prioritise drafting it if you haven’t.

You place these rooms, moving through them until you either are stuck placing only dead ends or run out of steps. Each day you’ve got a limited amount of rooms you can move through (including backtracking) and once that ends, your day is immediately over and you must restart with everything reset–other than any permanent upgrades you’ve managed to unlock or bonuses for the next day, which include new areas, upgraded rooms, and things like daily allowances of the game’s currency (gems and coins) or even extra steps.

If this sounds like a great piece of design–it is! Blue Prince has taken a format–the rogue-like-like deckbuilder–which isn’t always a slam dunk, and tied it logically to 3D exploration in a way that feels both surprising and exciting. The simple puzzle of putting the home together–trying to use dead ends in a way that doesn’t cut you off from the antechamber, placing rooms you haven’t seen before, hoping for the rooms you know you need–is “one more go” par excellence: you want to place another room, and each room leads to another. And if you fail? Dead ends, out of steps? Well, if you start again you’ll already get to place more rooms. So start again!

But here’s where respect comes in. Where, for me, the cracks begin to show. Because Blue Prince isn’t a “fair” Rogue-like-like. You can quibble the concept of fairness in games in the lineage of Rogue–after all, the original game is doubtlessly impossible to complete on the majority of runs–so let me state first that I believe that Rogue derivatives should aspire to every run being winnable. Doesn’t mean that the player wouldn’t have to play perfectly but it should be possible.

Why does this matter? I’m certain that a lot of people already disagree with me on this as a starting position–and if they’re already primed to defend Blue Prince, note that the game actually has an achievement for finishing it on a single run from a clean save, which I’ll get to. It matters because I’ve got an addictive personality. It matters because Blue Prince, more than any other game I’ve played, made me wonder why we love Rogue derivatives but hate loot boxes.

Yes, ok, loot boxes cost money. But Rogue-like-likes cost time. A game with loot boxes, sure, a whale can spend thousands–they miss a hit? That dopamine rush is just another spin away. A Rogue-like-like? You died, you made a bad decision, you didn’t get to the end? That dopamine rush isn’t just promised by completing the game. It’s soaked into the entire thing. You get a hit on every draw, every placement. Every tiny success is a tiny loot box being opened, chipping away at one big one offering success or failure.

But the trick is you fail on one, and that entire loot box is taken away. And in an “unfair” rogue-like-like, sometimes that bit loot box just contains “failure”. Nothing you could have done about it.

The game cost you an hour, maybe more, of your life, and said “give me more of your life. You’ll enjoy it. This time you might win! Think how good that would feel.”

Call this moralising if you like, but I know myself, and I find that promise very, very hard to walk away from even when you know the game is rigged. I’m good with money. I’m not good with time. I’m the king of time as a sunk cost–but I also know when I’m having my time wasted.

And Blue Prince wastes your time.

Look, there are many times in the game that you’ll make a mistake that will end a run. But I also had many runs where it either became obvious I couldn’t win–I never saw the object I needed for a room, or I never saw a room I needed full stop–or that the game just gave me a clear fail state: hands of dead-ends, or most egregiously, only rooms that would block off the antechamber (after I’d unlocked it!)

In these cases, the expectation is, I suppose, that you’re doing something else to help “build” your ability to win on the next run–a classic Rogue-like-like move. Setting aside that I had many (many!) runs where I was able to give myself nothing on the next run–many rooms that give you a “next run” benefit being dead ends or otherwise frustrating if you’re trying to “win” on each run–such design gives the game away that your time is being wasted. You weren’t going to win. Give Blue Prince an hour, it’ll give you a wee bonus next hour. Just one more hit. Aren’t you having fun?

The most egregious thing, however, is that in all of these cases I was trying to “win” the game by doing what it told me the “win” state was–entering the antechamber. I was aware there was a further “room 46” and that Blue Prince is a game of cascading mysteries, but I’m not sure I’ve ever experienced a “fuck you” as blatant as the experience of reaching the antechamber for the first time. I won’t detail it, but Blue Prince does nothing to celebrate or reward you for this, or really any wins. It’s not even justifiable as a critique of the Rogue-like-like loot box: it’s more like being told you’ve been given a present, and being given an near-endless Matryoshka gift box where when you get to the end there’s just a note that says “This isn’t the present.”

It really does feel to me like Blue Prince goes out of its way to waste your time. Much has been made of the “pay attention to everything” puzzles, which can have a cryptic crossword-esque trick to them, but the issue with them as with everything else in this game is that they’re a one-trick pony–and in a Rogue-like-like, you have to see the pony do that trick over and over again! I can see absolutely no reason why after I unlock a safe once I have to go to it and tediously type the code in again every run, but the nadir are the puzzle rooms, where you do things which are barely puzzles. I mean just weeks ago I was trying to find some good in Donkey Kong Jr. Math, where you just do simple math puzzles, but in Blue Prince there’s a room where you literally just do Donkey Kong Jr. Math-level puzzles over and over again! Even if you love Blue Prince’s core and don’t consider multiple runs a waste of time why would you ever want to do any of these puzzles more than once? It’s not like you’re doing something entertaining in itself, like a Picross or something. It’s just… do some maths!

Never mind that if you even want to understand a lot of the early game, you want the Magnifying Glass item, which I didn’t see on like my first… three or four runs (so hours into the game.) Meaning that in maybe my second go I’d unlocked a room, solved the puzzle that would allow me to look at things in that room, and then… gained nothing from it, because I didn’t have another item. I literally solved a puzzle and got nothing. Nothing!!! Too bad, RNG said no.

(To be completely fair to Blue Prince, what persists and what doesn’t is strangely inconsistent. A few rooms do keep things set between runs–probably because they involve such a huge amount of running between levers.)

This fucking thing.

Here’s my take, ultimately. A video game lives or dies on its mechanics. I’ve written previously on the transition between games as pure mechanics–you play them for the joy of play–and narrative–you play them to see the end. A Rogue-like-like is one of the purest attempts to split the difference, and the requirement, in my own framework, is that the game doesn’t misplace the “reward” (i.e. “I beat a run”) in the timescale of “I have seen either all the content or enough content to understand the systems so completely I am no longer surprised.”

Players who love the systems, get, with Rogue-like-like, the ability to play the game as long as they want–like an old school arcade game, almost. Players who want the experience, the reward, can move on feeling good rather than feeling beholden to it. A game like Slay The Spire or Balatro is successful–a winning run is possible from the start, and doesn’t individually take too long, but there’s far more depth if you want it. You can stop whenever you want, because there are no carrots to dangle. Just your own enjoyment.

The joy in Blue Prince’s mechanics becomes short-lived, and I don’t think so much because placing and exploring rooms isn’t fun–it’s because everything around it becomes such a pain. By my last runs, I was literally running full speed through the mansion, and every action I’d done a million times already felt like a punishment. But the insidious promise of success–that my luck would come around, that the RNG would release me–kept me there, like a drunk down bad at the blackjack table. You can say I should know how to walk away. I say: they’re done everything in their power to keep me there, and they aren’t even playing fair. Who’s really to blame?

Blue Prince didn’t respect me, so I stopped respecting it. It has all the worst impulses of Rogue-like-like design all wrapped up into a deceivingly attractive package, and I’ve left it with a completely oppositional viewpoint. I think this game tries to flatter you that you’re a genius while really it’s turned you into a rat mindlessly pushing a button hoping for treats, a donkey endlessly chasing a carrot that’ll never come.

Logic and reasoning are the reason we’re human, don’t waste them on this.

Will I ever play it again? No, and frankly, it did a lot to make video games feel like a completely waste of my time in general. A truly empty experience.

Final Thought: Above I mentioned that you can beat Blue Prince on a fresh save file. But obviously, no one could beat it first time and I believe, at this point, that RNG would make it impossible to beat the game every time even with full knowledge of the game first (though I’m willing to be proven wrong–it doesn’t change much.)

*Spoilers follow*

If you’re wondering when I explicitly lost respect for Blue Prince, it actually wasn’t when the Antechamber had a key and a note in it and not even like, an achievement for reaching it (a weak reward, but at least something.) It was when I discovered that the route I’d found to the underground (the fountain) using that key led to… an area where all I could do was move a minecart, and if I tried to change the lake height to get to the actual “endgame” I could no longer use that door. Which led to the realisation I could complete the game without ever actually going to the antechamber first.

I will give Blue Prince one point here–the game does feature a lot of different routes for solutions–but it’s really there I discovered Matryoshka gift boxes weren’t empty: they were a cascading collection of “fuck you”s.

For example–and this is likely to surprise anyone who has played this–I beat the game without ever placing the “foundation” room. Blue Prince’s RNG is so weirdly punitive I think I only saw it once, or twice, and didn’t place it as I needed other rooms (for real though, why is it a rare room. Why doesn’t it just always come up after the first few runs?) In the end I beat the game by using only the tomb and pump room, which requires an annoying amount of the game’s already annoying RNG and doesn’t even need the key, which made everything I’d spent so much time doing feel like even more a complete waste of time.

But I’m free now. And I’m never going back.

Developed/Published by: Nintendo

Released: 01/05/1984

Completed: 29/03/2025

Completion: Finished all 18 holes. *cough* 50 over par *cough*

Golf. Generally accepted as being invented in my home nation of Scotland, if there’s something we can all agree on about golf, it’s that it’s shit, a terrible use of land (and a terrible use of the huge amounts of water that is needed to maintain the courses on that land) but that it somehow makes for an entertaining video game.

I mean, you don’t have to take my word for it! It was banned multiple times even in Scotland as early as the 1400s because young men should have been practicing archery instead, and frankly, maybe if we hadn’t invented it maybe we’d still be an independent country. Although maybe that’s just a sign of not thinking outside of the box. Couldn’t our young men have turned their ability to hit balls with a stick into holes into some sort of a offensive weapon? By the time of golf gunpowder had reached Europe, so imagine pinging grenades towards the English front lines with deadly accuracy…

Uh, where was I?

Oh, yeah, golf. That it’s shit, but it makes a good video game.

Something surprising about golf is that despite it being one of the earliest kinds of games to be turned into a video game–as early as 1970, apparently, with Apawam, a text-based game for mainframes where you’d input your swing and see how close you got to the hole–there really isn’t much history online about it as a genre; it usually just gets shuffled under the umbrella of sports games.

Thing is–there were absolutely fucking loads of golf games in the early days of video games. It’s Pong-like in its ubiquity, but unlike Pong, which is… Pong, golf wasn’t as easy to “solve” for developers, leading to a variety of different interpretations. As usual, Magnavox put out a version as Computer Golf for Odyssey 2, and then Atari (basically) ripped them off with Golf for Atari 2600, but every one had a go, really: 1980’s PGA Golf for Intellivision, 1981 Data East had a go with 18 Holes Pro Golf in arcades, Taito in 1982 with Birdie King, and so on.

But it wouldn’t be until 1984 where it’s possible our old friend simultaneous discovery showed up that golf games would actually firm up into a genre, and while I’ve absolutely not done enough research (you go through every golf game in Mobygames’ list!) list it really does look like 1984’s Golf for Famicom–from the hand of Shigeru Miyamoto as designer and Satoru Iwata as programmer–is ground zero for what we now know as a golf video game, featuring probably the most important aspect: the “golf swing meter” where you have to hit the button three times: to start, to select your power, and then to manage the amount of curve on the ball by either getting it dead center or to one side–with the tension and skill being in if you can actually get the power and curve you want.

It’s hard to overstate how, even now, this simple mechanic makes Golf extremely playable. The game doesn’t feature any of the niceties of more modern golf games such as automatic club selection (which other games of the era managed, it seems) but it’s otherwise basically all there because golf really is this simple. You hit the ball, and then you hit it again until it goes in the hole, dealing with wind, hazards, and your own poor club choices or inability to get the timing right.

Golf is also a fondly remembered game in Satoru Iwata’s oeuvre, so much so that it was used in a rare (and limited) easter egg on Nintendo Switch. It wasn’t the first game Iwata worked on for Nintendo–according to a 1999 interview in Used Games magazine (via shmuplations) he toiled for two months on a Joust conversion that Nintendo ultimately couldn’t release then programmed Pinball. But it seems like Golf is where he made his name, doing something that no one else could do–fit an 18 hole golf course into the Famicom’s memory.

And it’s a good course! While there aren’t ever that many twists to a golf course, this one features easily understood tricks that make it fun to work out which club to use and how much power to go for–and a nice aspect of golf is that you can’t “fail” a playthrough, so you can just play all 18 holes with the worst possible score and then try again.

There are issues–the short game is near impossible, so you can find yourself racking up insanely high numbers of shots when you have to nudge your ball around rather than hit it any distance–and in the cold light of 2025 a single course isn’t going to keep you warm for very long. But almost every other golf game is inspired by this one, so if you want to play more of this but a different course… just play one of those!

Will I ever play it again? Probably not?

Final Thought: Interestingly, HAL would put out another golf game in 1984, Hole In One for the MSX. The game isn’t dated more specifically, but it’s interesting because it’s got a lot of suspicious similarities to Golf, but doesn’t do the single bar golf swing meter! It splits it into two bars, power and curve–though functionally it still requires three presses. It’s a strange decision, though I wonder if it was to try and simplify, or make clearer the the design compared to Golf.

Well, it didn’t stick–by the time of Hal’s Hole In One for SNES, they’d have gone back to the (by then) traditional golf swing meter.

The first American Masala.

…

Alright, to explain that a bit: I find something extremely moving about Indian epic cinema. At least partially it hits because of my own cultural connection to it, but it’s also that Indian cinema doesn’t treat their culture and traditions as rarefied specimen nor their history as sacred. They can gleefully mix melodrama, music, action and more to retell their stories in a way that suits them. The white man loves to hear about how bad he was and how noble the savages were in the face of everything they had done to them–and the kind of white man who sees that kind of film is very sorry now (but “look, it’s in the past now, and it’s not like we can fix what was done…”) but Indian cinema isn’t about that. It doesn’t revise or remix for pity. It says: we get to be the heroes of our stories. This isn’t about you. We’re cool as fuck. We’ve always been cool as fuck. So get reckt.

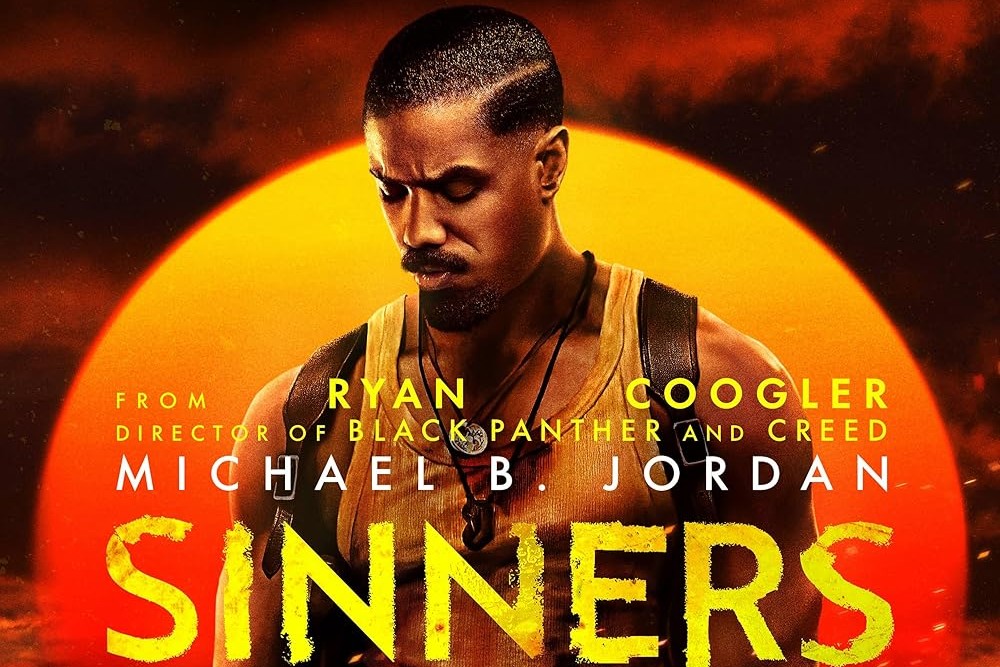

I have to admit that since seeing RRR I wondered if someone might take the baton of empowering historical revisionism and run with it for the Black American experience, and I’m thrilled that Ryan Coogler was able to escape the Marvel mines to create something like this–genre as cultural expression. Coogler explained himself that Sinners came from suffering the loss of his uncle:

“Coogler admitted that, for most of his life, he thought of the blues as ‘old man music,’ but that changed after his uncle’s death. ‘A mourning ritual for me, in a way [to] ease that feeling of guilt and loss, I would play these blues records,’ said Coogler. ‘But, I would play them with a newfound perspective, and I would kind of conjure my uncle.’”

And that’s it! Through our art, our experience of that art, we can conjure our ancestors and pay them tribute. Honour them. Show them love.

This is–obviously–barely subtext in Sinners. I suspect if you’ve been used to seeing yourself on screen the centrepiece musical sequence of this movie probably seems silly. And to be honest, Sinners is often ridiculous! But I felt nothing but a deep sense of solidarity watching this: a movie that doesn’t say “look at what we suffered” but “look at how we endured. Look at what you can never take away from us…

…and look at what we’ll do to you if you ever try again.”

Follow Mathew on Letterboxd.